Palestinian people and the Black people of the Caribbean know the necessity and the consequences of their resistance, how it activates the spirit of revolt in oppressed people everywhere.͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ When we think of the connections between the Black struggle and the Palestinian struggle, we forget to say Haiti, we forget to say Grenada. But in the resonances between these histories, there is so much we urgently need to hear today. Palestinian people and the Black people of the Caribbean know the necessity and the consequences of their resistance, how it activates the spirit of revolt in oppressed people everywhere. Both peoples know what it means and what it costs to break out of the colonizer’s prison. The first successful revolt of black slaves in history began in August 1791 in what was then called “Saint-Domingue” and is now called Haiti. Under the military leadership of Toussaint L’Ouverture, the revolt became a full-blown revolution, culminating with national independence in 1804 — a year after L’Ouverture died a martyr in his prison cell in France — and making the logic of freedom infectious. The Haitian Revolution was a total overthrow not only of the French regime, but also of the colonial assumption that the enslaved could never gather the strength to resist subjugation. Clash by clash, the coming victory sang across the waters. All across the Caribbean, enslaved people could hear the tones of the uprisings. In 1795, the island of Grenada lit up with a resounding demand: freedom from British rule and the tyranny of slavery and colonization. In Haiti and Grenada, the owner class could not hear the threat of freedom until the bell had been rung. There was blood. There were sacrifices. But the Grenadian people, in the nascence of their movement toward independence, created new conditions for the possibility of revolution. Fédon’s rebellion inspired a second revolution in 1979, led by the New Jewel Movement of Grenada in response to the encroachments of U.S. imperialism on the limited independence Grenadians had won. Grenada, like Palestine, was a victim of geography, a land that superpowers saw as a geopolitical tool. The Black Liberation movements of the Caribbean islands are cousins of the Palestinian national liberation struggle. They share a DNA of resistance. The history of Palestine’s uncompromising resistance to colonial domination did not begin on October 7th, just as Grenada’s did not begin in 1983. All three of these histories, Grenada, Palestine and Haiti, cross each other at intersections that map the pursuit of freedom and the fact of endurance and determination. The realization of freedom is on the horizon for Palestine, just as it remains on the horizon of Haiti and Grenada. This is a call for the recognition of a solidarity that spans generations, and spans the globe, from the East to the West. Black people and Palestinian people know what it means to suffer from the costs of revolution, all know intimately the grueling cost of resisting colonization and occupation. All suffer from the persistence of their people’s lives. But at the end of the long fight for freedom is a fever dream realized.

Was this email forwarded to you? Sign up to receive it here. |

Think differently about prisons |

The New York War Crimes recently published an interview with social anthropologist Orisanmi Burton about the Palestinian captives movement and the Attica rebellion. Referencing prison intellectual Walid Daqqa’s text “Consciousness Molded or the Re-identification of Torture,” Burton demonstrates how Zionist colonialism, itself long described as a form of incarceration, asks us to “think differently about what prisons are.” Read an excerpt below and the full interview here. NYWC: Per the article’s title, Daqqa specifically discusses Zionist prisons as a form of psychological warfare, in addition to physical attacks like beatings and sleep deprivation. Why does Daqqa argue that “consciousness remolding” is the primary aim of Zionist prisons, and how does this relate to the forms of psychological warfare waged against prisoners during the Attica uprising? There are differences here between the kinds of internal colonialism that Black people are subjected to and the kinds of settler colonialism that Palestinians are subjected to. In our case, historically, we were needed, the ruling authority kind of needed us for different reasons, right? They needed us for labor. They also needed us psychologically. And so the goal then was to preserve the body, but to break the spirit, to destroy the inside, to destroy the will, to destroy the desire for independence, to destroy the imagination. To turn us into something else that served their needs. That's the kind of genocide that Black people have been subjected to here. Queen Mother Moore talks about that in the beginning of the book. Imam Jamil Al-Amin, H. Rap Brown, writes about this in Die Nigger Die!, his autobiography. In the context of Palestine, I think [the Zionists] need Palestinians, but in a different kind of way: they serve psychologically as an external enemy that helps create ethnonational cohesion. They’re the enemy that's always surrounding Israel, right? This idea of Israel, and that constant fear mongering, helps to create internal solidarity which otherwise may not exist. At the same time, Palestinians are also targeted for elimination, because that's how settler colonialism works. However, obviously, there's also this long tradition of Palestinian resistance--like, just getting rid of them isn't that easy, right? And different tactics have been used throughout time. What's so important about Daqqa is that he's targeting these more subtle mechanisms which are less identifiable immediately as violent modes of subjection. So he's not talking about assassination, but we know that happened. He's not talking about the brutal forms of torture, although we know that happened. He's talking about the subtle ways that Zionist prisoncrats have tried to destroy the Palestinian nationalist consciousness, to destroy the idea of a Palestinian, to destroy the idea of a unified Palestinian people. |

Throughout Israel’s genocidal assault on Gaza, Palestine solidarity protests at historically Black colleges and universities have often been overshadowed or elided in news coverage of student activism. However, significant protests have taken place at major HBCUs like Howard, Clark Atlanta, Spelman, North Carolina A&T, and Morehouse. During then President Joe Biden’s address at Morehouse’s commencement, a number of students wearing keffiyehs turned their back on him in protest of his administration’s perpetration of genocide in Gaza This lack of coverage is partially due to a lack of encampments at HBCUs, owing to a long history of harsher disciplinary measures and social movement repression on those campuses, but the elision of Palestine activism by HBCU students has a deeper cause. For one, HBCUs have long been recruiting centers for the armed forces, military intelligence, and international diplomacy, and thus served a critical role in incorporating Black political leaders into American imperialism. Additionally, it often goes unremarked upon that HBCUs have consistently educated a vastly disproportionate amount of Black professionals and political leaders, and continue to wield immense influence in Black political life in the United States. As affirmative action and DEI come under attack in the United States, it is likely that HBCUs will see increased enrollments, but also come under deeper pressure and scrutiny from the Trump administration and its allies, including Zionist organizations which seek to stifle international Palestine solidarity. Thus, Palestine solidarity amongst students at HBCUs (which have also seen growing enrollment of Latino students) is tremendously impactful and strikes directly at the heart of empire by threatening the mechanisms via which Black political leaders become incorporated into complicity with Zionism and American imperialism. In the years to come, HBCU students will play a vital role in the worldwide struggle for freedom as the American empire degrades and collapses. |

From Palestine to the United States, release all political prisoners! Political prisoners in the United States and in Palestine have moved in solidarity with each other. In one famous instance, Khader Adnan released a statement of solidarity with tens of thousands of hunger strikers in prisons across California. Adnan died in an Israeli prison in 2023 after nearly 3 months of hunger strike. Political prisoners in the U.S. have likewise supported Palestine. We have compiled a few writings on Palestine from political prisoners in the United States for you to read. While reading through these, we invite you to support the RAPP (Release Aging People from Prison) Campaign which aims to “end the racist law-and-order policies that have more than doubled the number of elders behind bars over the past 20 years, to expand the use of parole, compassionate release, and clemency, and to end life imprisonment.” Read more about RAPP’s active campaigns and sign up to join their work in New York State here. |

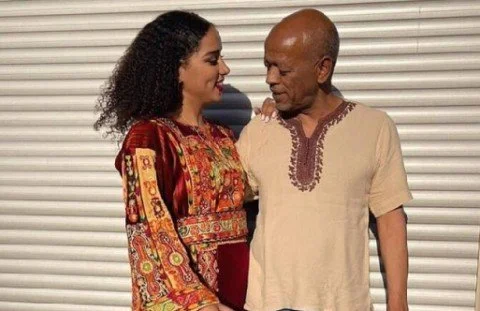

We leave you with the words of Afro-Palestinian artist, activist, and law student Shaden Qous: “The occupation is not eternal. As long as we continue to adhere to our national rights and believe in the justice of our cause, sooner or later, we will regain our freedom. We are not living on the margin of history. Our generation is aware of its cause and very well educated.” Shaden Qous is also the daughter of Mousa Qous, the beloved Jerusalem writer and comrade who died in a fire earlier this month. In January, Shaden was detained by the IOF and prevented from attending her father’s funeral. She has since been released. Read the aforementioned quote in context, as published in Mousa Qous’s full story about Afro-Palestinians in Jerusalem on community, folklore, prisons, and resistance here. |

1) Grenada Committee for Popular Education. 2) Drawing by Walid Daqqa. 3) Howard University Student Protest for Gaza. 4) Shaden Qous and her father Mousa |

|

|

|