Nabil Anani (Palestine), In Pursuit of Utopia #1, 2020.

Dear friends,

Greetings from the desk of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

On 15 February 2024, Jared Kushner (Donald Trump’s son-in-law and former senior advisor during his presidency) sat down for a long conversation with Professor Tarek Masoud at Harvard University. During this discussion, Kushner talked about ‘Gaza’s waterfront property’, which, he said, could be ‘very valuable’. ‘If I was Israel’, he continued, ‘I would just bulldoze something in the Negev [desert], I would try to move people [from Gaza] in there… [G]oing in and finishing the job would be the right move’.

Kushner’s choice of the Negev, or al-Naqab in Arabic, is interesting. Al-Naqab, located in what is now southern Israel, has long been a place of tension and conflict. In September 2011, the Israeli government passed the Bill on the Arrangement of Bedouin Settlement in the Negev, also known as the Prawer-Begin Plan, which called for the eviction of 70,000 Palestinian Bedouins from their thirty-five ‘unrecognised’ villages. Kushner is now advising Israel to illegally shift even more Palestinians to al-Naqab, many of whom were originally pushed to Gaza from cities in parts of Palestine that are now within Israel. As Kushner might know, both a population transfer to al-Naqab and the seizure of Gaza are illegal according to Article 49 of the 1949 Geneva Conventions.

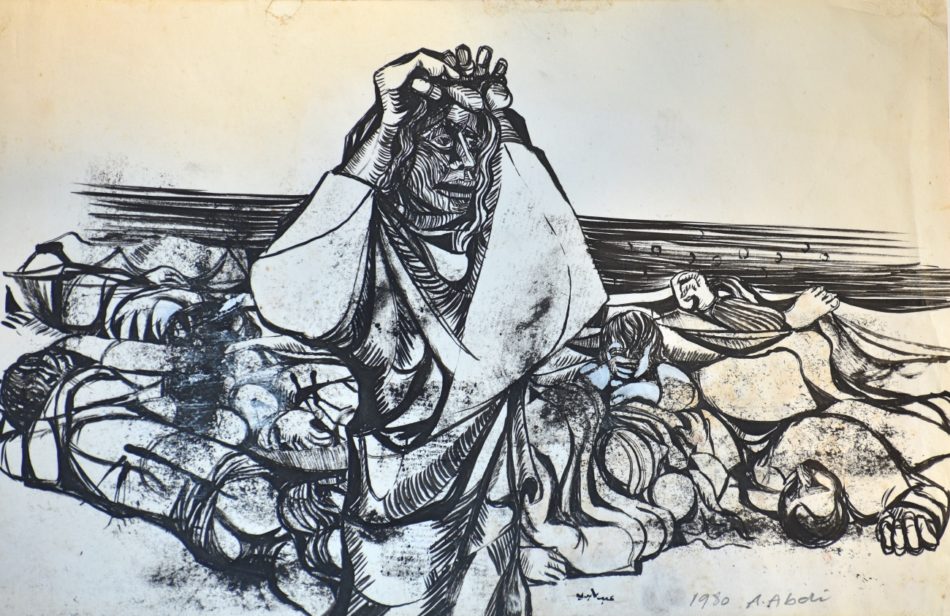

Abed Abdi (Palestine), Massacre in Lydda, 1980.

The displacement that faced Palestinian Bedouins in 2011 and that faces Palestinians in Gaza today is reflective of the plight that has been inflicted upon Palestinians since the creation of the Israeli state in 1948. Every year since 1976, Palestinians around the world have commemorated Land Day on 30 March, marking the killing of six Palestinians during a mass action to fight an attempt by the Israeli state to eliminate Palestinians from the Galilee region and carry out Yihud Ha-Galil (the Judaisation of the Galilee). The Israeli regime has tried to annex all of the Galilee and al-Naqab since 1948 but faced fierce resistance from Palestinians, including Palestinian Bedouins. Israel’s violence has failed to intimidate and cleanse the region for the establishment of Greater Israel (Eretz Yisrael Hashlema) from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea. Israel has not been able to attain its aims. It cannot eliminate either the Palestinians or the Bedouin. Its dream of a pure Zionist state is futile.

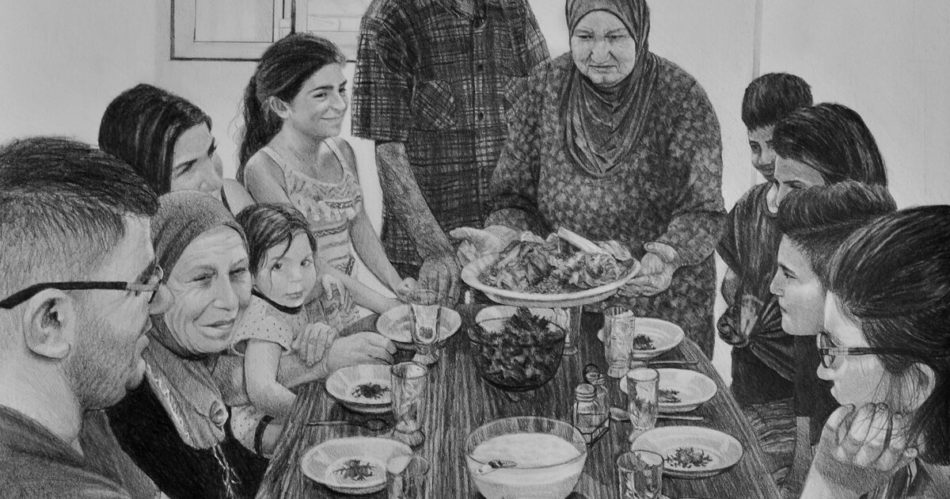

Samah Shihadi (Palestine), Mansaf, 2018.

On 9 December 1975, the Palestinian population of Nazareth elected Tawfiq Zayyad of the Communist Party (Rakah) with 67% of the vote. Zayyad (1929–1994), a well-regarded poet, was known as ‘The Trustworthy One’ (Abu el-Amin) for his ceaseless role in forging a united front amongst Galilee Palestinians against the Israeli policy of forced evictions. For these activities, Zayyad was arrested on numerous occasions, but he never wavered. Zayyad joined the Communist Party in 1948, became the head of the Arab Workers’ Trade Union Congress of Nazareth in 1952, led the party in his hometown of Nazareth, won a seat in the Knesset (Israeli parliament) in 1973, and then became the mayor of his city in 1976 as the candidate for the Democratic Front for Peace and Equality. His victory, which surprised the Israeli establishment, was hailed by the Palestinians of Galilee, who had been fighting against the attempts to steal their land and homes since 1948.

In 1975, the Israeli authorities announced that they would expropriate 20,000 dunums (18 million square metres) of Arab land, mostly in central Galilee or ‘Area 9’, which meant the extinction of the villages of Arraba, Deir Hanna, and Sakhnin. These were not new plans. Beginning in 1956, Israel created cities to displace Arab villages around Nazareth such as al-Bi’neh, Deir al-Asad, and Nahef: first, it created Natzeret Illit (known as Nof Hagalil since 2019), and then, in 1964, it created Karmiel.

When I visited Nazareth in 2014, I was taken for a walk around the city’s perimeter to experience how the new Jewish-only settlements were designed to throttle the old Palestinian city. Haneen Zoabi, then a member of the Palestinian party Knesset for Balad, told me about how Nazareth, where she was born, has, like the West Bank, been gradually squeezed by illegal settlements, the apartheid wall, checkpoints, and regular attacks by the Israeli military.

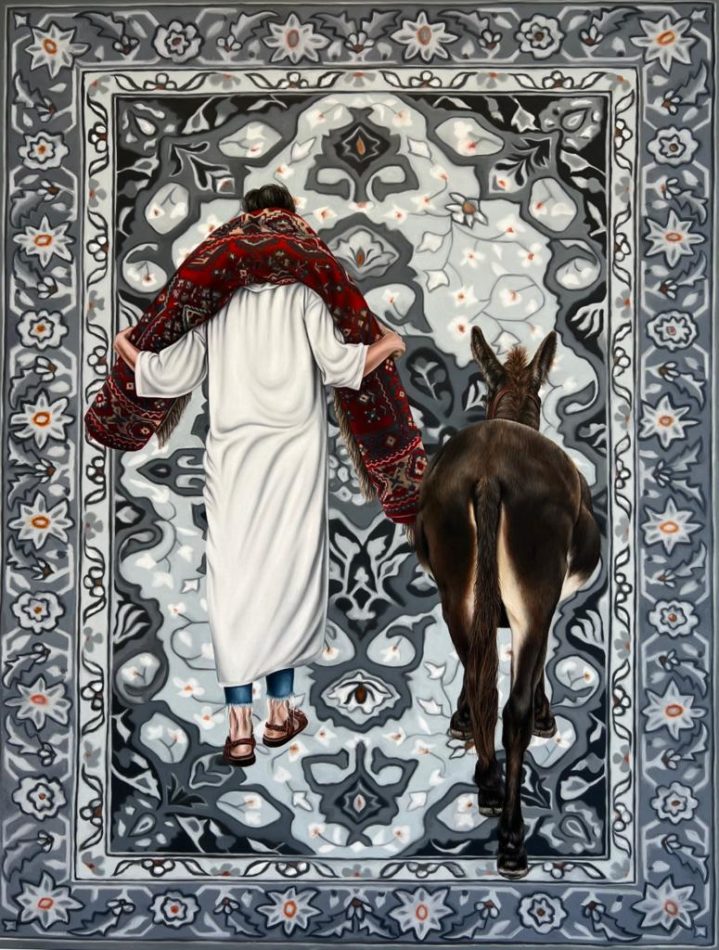

Fatma Shanan (Palestine), Two Girls Holding a Carpet, 2015.

Before the general strike could get going on 30 March 1976, the Israeli regime sent in a full contingent of armed military and police to ruthlessly beat unarmed Palestinians, injuring hundreds and killing six. Tawfiq Zayyad, who led the strike, wrote that it was ‘a turning point in the struggle’, since it ‘caused an earthquake that shook the state from end to end’. The Israeli regime planned to ‘teach the Arabs a lesson’, Zayyad wrote, but that ‘caused a reaction far greater in its effect than the strike itself. This was demonstrated at the funerals of the martyrs who fell in the strike, which were attended by tens of thousands of people’. That day became Land Day, which is now part of the calendar of the struggle for Palestinian national self-determination.

The Israeli regime was undeterred by public outcry. On 7 September 1976, the Hebrew newspaper al-Hamishmar published a memorandum written by Yisrael Koenig, who had administered the North District, including Nazareth. Koenig’s thoroughly racist memorandum called for Palestinian land to be annexed on behalf of fifty-eight new Jewish settlements and for Palestinians to be made to work through the day so that they would have no time to think. Israel’s prime minister at that time, Yitzhak Rabin, did not repudiate the memorandum, which also detailed plans for the Judaisation of the Galilee. The plans never ceased.

In 2005, the Israeli government decided that the deputy prime minister would administer the Galilee and al-Naqab. Shimon Peres, who held that post, said then that ‘[t]he development of the Naqab and the Galilee is the most important Zionist project of the coming years’. The government set aside $450 million to transform these two regions into Jewish majority areas and expel Palestinians, including the Palestinian Bedouin, from them. That remains the plan.

Fatima Abu Roomi (Palestine), Two Donkeys, 2023.

Jared Kushner’s statements are easy to dismiss as a fantasy since they contain a measure of ridiculousness. However, to do so would be misguided: Kushner was the architect of Trump’s Abraham Accords, which led to the normalisation of Israeli relations with Bahrain, Morocco, and the United Arab Emirates. He also has a close relationship with Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu (who used to stay in Kushner’s childhood bedroom in Livingston, New Jersey).

Al-Naqab is a hot desert, a place that remains sparsely populated even after the expulsion of many of the Palestinian Bedouin. But Gaza has possibilities as a seaside resort and as a base for Israel’s exploitation of natural gas reserves in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. This accounts for the sustained attention it has received within the Zionist agenda, represented in Kushner’s blunt statement. But, if history is any judge, it is unlikely that the Palestinians will move from Gaza to al-Naqab or even the Sinai desert. They will fight. They will remain.

In September 1965, after he returned to Palestine from Moscow, Tawfiq Zayyad wrote the poem ‘Here We Will Remain’. It was published the next year in Haifa by al-Ittihad Press alongside his classic ‘I Shake Your Hand’, which was put to music by the Egyptian singer Sheikh Imam and memorised by Palestinian children across the world (‘my hand was bleeding, and yet I did not give up’). The events of 1976 strengthened Zayyad’s popularity in Nazareth, where he remained the mayor till his death in 1994. Tragically, he was killed in a car crash as he returned from the West Bank, where he had gone to welcome Yasser Arafat to Palestine after the Oslo Accords. Thinking of Land Day, and thinking of Gaza, here is Comrade Zayyad’s ‘Here We Will Remain’:

In Lidda, in Ramla, in the Galilee,

We shall remain,

Like a wall upon your chest,

And in your throat

Like a shard of glass,

A cactus thorn,

And in your eyes

A sandstorm.

We shall remain,

A wall upon your chest,

Clean dishes in your restaurants,

Serve drinks in your bars,

Sweep the floors of your kitchens

To snatch a bite for our children

From your blue fangs.

Here we shall remain,

Sing our songs.

Take to the angry streets,

Fill prisons with dignity.

In Lidda, in Ramla, in the Galilee,

We shall remain,

Guard the shade of the fig

And olive trees,

Ferment rebellion in our children

As yeast in the dough.

Warmly,

Vijay